A

Healthy Forest Grows a Tree

As

told by Larry KrotzĀ (then heavily

edited by Cindy and Scot Heisdorffer)

IÆll

begin with a brief description of my growing strategy.Ā It isnÆt reasonable or practical for me to

think that I can consistently grow perfect trees.Ā There are simply too many contributing

variables that I canÆt control.Ā However,

something over which I have at least partial control is the growing

environment, for example, canopy and seedling density.Ā So, my primary focus is to establish and

maintain an optimal growing environment, once IÆve determined what that is, and

thereby allow the forest to produce the best trees possible.Ā Success!

IÆll

begin with a brief description of my growing strategy.Ā It isnÆt reasonable or practical for me to

think that I can consistently grow perfect trees.Ā There are simply too many contributing

variables that I canÆt control.Ā However,

something over which I have at least partial control is the growing

environment, for example, canopy and seedling density.Ā So, my primary focus is to establish and

maintain an optimal growing environment, once IÆve determined what that is, and

thereby allow the forest to produce the best trees possible.Ā Success!

But then, how does a

tree farmer define success?Ā That is not

an easy question to answer.Ā There is no

one-size-fits-all definition.Ā Also, it

is likely that, over a period of time, an individual farmerÆs definition can

evolve.Ā I know mine certainly has

evolved since I started to grow trees in 1962.Ā

In the beginning, it seemed as though trees were considered a cash crop,

like corn or soybeans, to be harvested periodically in order to generate

income.Ā I no longer share that

perspective.Ā My current definition of

success stresses the importance of long-term, self-sustaining,

transgenerational growth over short-term financial gain.Ā I believe that both perspectives fulfill a

need, the former financial, the latter aspirational.Ā I now aspire to establish and nurture my own

permanent and stable forest, though, not a wilderness area, one that will exist

into the 22nd century and beyond.Ā Block

areas of trees will be clear cut harvested for financial gain as they reach

maturity and replanted for another cycle of this long term rotational forest

crop.Ā The hard-earned lesson that I have

learned over the past six decades of tree planting is that trees tend to grow

the best when they are left on their own as nature intended, when human

interaction is therefore minimized or ideally eliminated altogether.Ā The following narrative retraces the

evolution of that lesson.

I am a retired

Aeronautical Engineer, a retired United States Air Force fighter pilot, and now

a tired active-duty tree farmer. IÆve accidentally developed a fascination and

addiction for trees and how to best grow them, not only because I really enjoy

the trees themselves, but I love the many products made from them.Ā Black walnut is my favorite wood for carving

and woodworking, thus it has become a particular passion.Ā

My career as an

engineer was very short.Ā I graduated in

June of 1957 as an Aero E. and a commissioned USAF 2/Lt qualified for pilot

training.Ā For strictly financial reasons

I initially requested a delayed reporting date for my 5-year active duty

commitment.Ā I was making $550/month as

an engineer vs. $222/month as a pilot. This was, of course, during pre-computer

days when using an offsite main frame was standard procedure.Ā I soon became disenchanted with the dull and

repetitive task of operating a Monroe Calculator manually processing

aerodynamic formulas for designing wings for anti-missile missiles.Ā Frankly I was just plain bored.Ā This boredom, along with Defense Contracts

threatening my job in January 1958, changed my life.

I requested an earlier

training date and started pilot training in March 1958, graduating in December

1959, as a fully qualified F86 fighter pilot.Ā

I was literally flying high and on top of the world.Ā I thus found my niche and decided never to go

back to engineering.Ā This dream come

true was, however, not to last.Ā Less

than two weeks later the AF suddenly discovered they had a surplus of pilots

and consequently started to downsize.Ā I

got caught in the big shuffle, so for the next several years I bounced around

from one deactivating squadron to the next.

In early 1962, I was

stationed in Madison, Wisconsin, and leading the life of a frustrated deskbound

fighter pilot.Ā I was planning a big

change, however.Ā My wife Sandy and I had

just purchased a 235-acre farm in southeast Iowa.Ā I planned to farm, fly with the airlines to support

farming and its captivating lifestyle and join the Des Moines Air National

Guard for the pure joy of flying. The AF was supposed to be in the process of

transitioning to F104Æs (a very hot airplane at the time that was more like a

man in a rocket). ĀI was looking forward

to that.Ā But it was really the purchase

of farmland that marked the official start of my tree addiction.Ā I started to dream of small woodlands where I

would someday plant walnut trees.ĀĀ

Shortly after this farm

purchase, the Cuban Missile Crisis put me back in the cockpit of a F102 fighter

aircraft. The AF now needed pilots. The feast to famine routine changed

again.Ā My plans with the airlines and

National Guard disappeared and would never return.Ā I was, however, still intensely enthused

about increasing the number of trees on the farm.Ā (At that time there were fewer than

300!)Ā For the remaining year and a half

prior to the change of station every chance I could, I planted trees.Ā Madison was only 200 miles away from the farm

so the planting was done on the few available duty-free weekends.

In these first years of

planting I put a few black walnut nuts around a newly installed pond area, and

I also manually planted a few seeds in the permanent pasture where the cows

grazed, an idea that turned out to be quite ignorant.Ā I also installed conifers for a windbreak,

but they quickly died out.Ā At this point

grazing cattle, mowing to control weeds, planting too late in the season,

drought, etc. were all thwarting me, as well as a general lack of knowledge

about what I was doing.Ā It was not a

real promising start. This is while I had watched farmers in the Madison area

planting conifers in abandoned farmland that flourished with no apparent care.Ā Why couldn't I do that?Ā Much later I was to discover these farmers

had received much more timely annual moisture.

In late 1964, I moved

to Texas as an instructor in advanced flying school.Ā I loved the new job, but I hated the much

longer commute to plant trees.Ā I tried

planting Texas pecan trees, but they perished in the first Iowa late spring

frost, which is when I discovered latitude change makes a difference for plant

material.Ā It was then that I started to

read books and pamphlets that I had ordered from the Dept. of Agriculture. One

pamphlet in particular on black walnut suggested planting a monoculture of

black walnut seedlings as a plantation.Ā

I continued to struggle, planting seedling transplants, primarily

conifers and walnut seedlings and nuts, with very discouraging results. I also

planted quite a few volunteer seedling trees from my Aunt Lena's flower

beds.Ā The trees would be flourishing in

the flower bed, and would stay alive after transplanting, but these trees never

had the same degree of vigor.Ā (You will

recognize later in my story that this was the light bulb starting to

illuminate.)Ā Initially I planted a

couple hundred trees a year, gradually increasing this amount every year, but

with very poor survival rates.Ā I had

planted every year until 1967 when I was ordered to Vietnam, followed by

consecutive European tours ending in December of 1973.Ā All tree planting halted for this entire

six-year period.

In late December of

1973, I was again stationed in Texas, so I was able to resume planting trees

from long range.Ā The spring of 1974 my

brothers and I ordered 36,000 seedling trees to plant on 4 farms, some as

windbreaks and the rest as forestry projects.Ā

(As an aside, the vast majority of this planting took place on my

brothersÆ farms as I really wanted to encourage them to plant more trees as

well.)Ā I took a long leave and we

struggled to get all those trees in the ground in less than a 2-week period of

time.Ā My brother converted an old corn

planter to install seedling trees.Ā That

machine, along with the manual hand planting using the virtual slave labor of

my brothers, Dad, and an army of approximately 20 school kids I happily called

my "highly skilled technicians" worked well enough.Ā I considered it a success when most of the

seedlings were in the ground right side up!Ā

After all my failures from earlier times, we had some surprising results

with survivability on a good percentage of those trees that were so thickly

stuck in the ground.Ā I did not know it

at the time, but I was then on the road to high density planting.Ā Much later I realized that we had accidently

picked a perfect year for planting.Ā

Cool, moist conditions and timely rainfall throughout the first growing

season really helped our efforts.Ā

Regrettably, initial

successful survival rate was not to last in large portions of the plots.Ā My dad and brother-in-law, both of whom were

incredibly helpful, simply could not stand weeds and they decided to mow

between the rows of trees.Ā These rows

were hard to clearly identify and many trees were mowed out or damaged.Ā This solidified my aversion to mowing as a

primary corrective measure for weeds.Ā

Since then I have found that some weeds can even be beneficial.

And so it went from

1962 until 1978, trial-and-error planting without a whole lot of good results

for my efforts.Ā I made many, many

mistakes, and although I probably didnÆt manage all the mistakes humanly

possible, it was definitely getting close.Ā

I retired from the AF

in the spring of 1978 and could potentially start to devote nearly all my time

to planting trees.Ā I was supposed to be

building our future house, but I had not yet learned the magic word ōnoö when

requests for help came my way.Ā I ended

up spending much of my time helping my brothers on their farms, and building

our house became secondary, so I was the definition of someone with too many

irons in the fire.Ā I was able to spend

only small portions of time planting a few more trees.Ā I did manage to fence off a section of my

permanent pasture from the cows once I realized their wanderings had caused

soil compaction to the degree that some of the old hickories were starting to

die off and that cows had browsed the trees planted in the pasture in earlier

years.Ā In the small amount of time I set

aside for more tree planting, I hand-planted a few 5-gallon buckets of walnuts

along the creek.Ā I would just strap a

pail around my waist with a piece of twine, fill it with hulled walnuts which

are easier to plant manually (they are lighter and smaller without the hull),

make a 45-degree angle slit in the ground with a long-handled shovel and simply

toss in a nut.Ā Much later I was to find

out that these trees had survived and even appeared very happy in their

surroundings.Ā They had a little help

from nature in the form of "trash trees" accidently becoming nurse

trees.

In 1982, I had all

cattle removed from the 65 acres of pasture, leased the land that had always

been used for crops, and now my dream of having that pasture changed to

woodland was going to happen . . . slowly.Ā

This was my 20th year of struggling with trees.Ā My neighbor disked 2.5 acres of bottom land

so I could seed direct into soil that was free from sod.Ā Black walnut was the most valuable, so why

should I waste time planting anything else?ĀĀ

During this particular time, I was led to believe that black walnuts

should be grown in heavily managed monoculture plantations.Ā I didnÆt like that, but I was going to try

one more time for a walnut plantation that I could cultivate and keep free of

weeds.Ā Maybe this tactic would somehow

change soil conditions enough to allow the walnuts to start flourishing.ĀĀ

I laid out precise rows

9Æ apart with 4Æ spacing of seeds and staked the rows for later row

identification. I used seed since it was readily available versus relatively

costly nursery stock.Ā In the spring of

1983 I had to wait for the first seedlings to emerge to see the rows (cows had

knocked most of the stakes down the previous fall prior to their removal). ĀI then lightly cultivated with a towed 8Æ disk

between the 9' rows.Ā This was a disaster

from the very beginning due to all the damage I was doing to both roots and

tops.Ā It was an embarrassing and

hair-brained scheme and I walked away from it.Ā

Later in the year I gathered a bunch of seed, mostly elm, box elder and

hackberry, and broadcast it over the 2.5 acres.Ā

This was supposed to be ōmy carefully tended plot growing quality

walnutö?Ā I was most certainly

discouraged.ĀĀ (I had also planned on

seeing if I could grow a walnut with a clear bole of 30Æ without manually

pruning.Ā I still have that goal, but IÆm

not quite there.)

In previous years, I

had been mainly using seedling transplants with a few seeds between

transplants.Ā After the first few years,

a seedling transplant would generally grow but seldom would continue the

original terminal growth for the first year after transplant.Ā In most cases the sapling would shoot 3-5

side buds that first year rather than continue the original terminal growing.Ā That was unacceptable for me because it would

require later pruning.Ā I wondered if

this could be something to do with epicormic sprouting since this small

transplant is most certainly under stress.Ā

Every time we transplant a tree, we have a ratio of 100% of the top and

maybe 40% of the root.Ā Most of the very

fine feeder roots are destroyed with exposure to air during transplant.Ā Until the plant has a chance to replace those

feeder roots, it is my experience that the tree will not resume normal growth.Ā During this time frame I noticed the

transplants were not flourishing while the occasional seed I would put in was

looking great.Ā In fact, the seed direct

tree always looked more like the very healthy trees growing in my Aunt Lena's

flower bed.

Within this time frame,

there were a couple of noteworthy ideas beginning to form.ĀĀ I was starting to recognize the relationship

between planting very large numbers of trees and the quantity of excellent

trees.Ā I also began to be a bit more

partial to planting deciduous trees over so many conifers, for a variety of

reasons that will simply make this story too long!Ā I began to think about the importance of the

canopy in suppressing the non-native perennial sod-forming grasses (canary

grass and brome grass), the soil conditions in terms of moisture and

temperature, and finally the way plants grow when thereÆs shading in that they

are growing far more vertically than horizontally. I also started to learn more

about herbicides and trust I could use them properly.Ā This was the time I realized I really wanted

my trees to flourish rather than just survive.

Ā

Ā

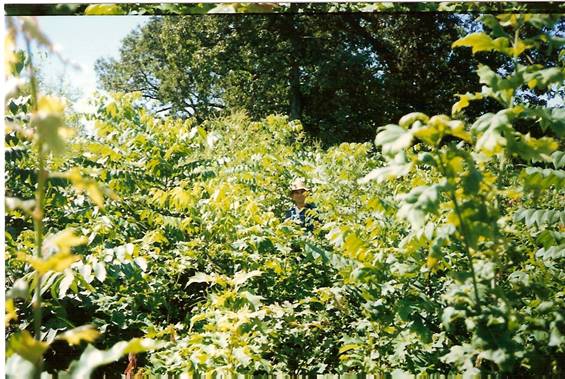

IÆve observed that

natureÆs model for healthy forests is the most reliable.Ā These photos above show the top and bottom of

a tree in my monoculture plantation that was rescued by introduction of so

called ōtrash treesö. The tree has completed 32 years of growth and has never

been manually pruned. I had pruned back an occasional box elder or elm that was

interfering.

ĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀ

In 1983, I planted a

large number of conifers in the permanent pasture that had been taken out of

grazing.Ā The sod-forming perennial

grasses were out-competing the trees that I was planting.Ā I noticed that once conifers got past that

first year after transplant (as long as they were thickly planted), they were

more likely to grow without human intervention.Ā

I was planning on a conifer/black walnut companion plant

plantation.Ā The reason for this was to

ensure that the conifers provided the grass control as the black walnuts could

not do that on their own.Ā I hand planted

these conifers in the very early spring (this is important in order to minimize

disturbance) into old growth bluegrass and then a smaller quantity in a

manicured area (our lawn).Ā 1983 was a

severe drought year and there was a remarkable difference in survivability of

these small conifers.Ā In the well-tended

areas, the trees were watered throughout the season and most of them still did

not survive.Ā In the old growth

bluegrass, where there was no tending whatsoever,Ā the loss ratio was noticeably smaller.Ā I therefore concluded that not mowing the

bluegrass had allowed the grasses to set seed pods, after which the plant

simply went dormant until late fall when it started to really grow again in

order to prepare for the next season.Ā In

the interim, the tall dormant grasses were not using a lot of nutrients and,

even more important, the 18-24ö dormant grasses had in fact shaded the ground

and tended to keep the soil temperature much lower.Ā Cool, moist soil in the root zone seemed to

be the key.Ā The second principle

involved was aerodynamics, an effect similar to what blow dryers in restrooms

achieve.Ā By not mowing the grasses in

the root zones, small barriers to airflow were not eliminated.Ā The loss of soil moisture was reduced by

slowing the airflow during the hot summer months.Ā So, if stalks of grasses can reduce the

airflow which in turn reduces moisture loss, a larger quantity of trees should

be able to achieve the same result over a potentially much more extensive area

of land.Ā This conclusion thus convinced

me that tree stems planted in high density tended to favor high yield.

This high density, or

ōcrowded effect,öĀ required a great

number of trees, many more than were considered normal at the time.Ā When I first started planting trees in

1962,Ā a forested area comprised 200

trees per acre.Ā That might still be

true, but only when the trees are 40 to 50Æ tall.Ā It most certainly is not true, however, when

the trees are merely 1 to 2Æ tall.Ā At

the initial stage of planting, that little tree is rather lonely in this huge

prairie setting. This is by no means a forest, even if there are 1000 trees per

acre.Ā I now firmly believe that, in

order to improve my success rate,Ā I need

to plant thousands of trees, so my monetary expenditure subsequently increases.

Ā

In order to avoid the

intimidating expense of purchasing thousands of seedlings, I decided to start

my own nursery, growing deciduous as well as coniferous seedlings that could

serve as companion trees for the walnut.Ā

I really didnÆt know what I was doing, so there was a lot of trial and

error.Ā I collected and stored seeds of

all types, some in unintentionally unfavorable conditions for staying

viable.Ā I quickly got to know where all

the best seed collection sites were located, not just in my county, but also in

a few surrounding counties.ĀĀ I raked,

swept or used a nut picker.Ā Whatever the

most efficient method of collecting was, I used it.ĀĀ Interested spectators with whom I talked

during these nut-gathering excursions frequently suggested contacting their

friends for additional collection opportunities.Ā In many cases they would have the seed

already collected and were extremely pleased to let me haul it off.Ā Sadly, some of this seed was collected and

stored improperly.Ā I now know what

happened:ĀĀ Under no circumstances should

black walnuts or acorns be collected and stored in a plastic lined bag on hot

September days because they tend to lose viability in a hurry.

My nursery produced

mixed results.Ā A most important lesson I

learned was no matter how much dead seed you plant, youÆre not going to get

live trees!ĀĀ I remember my dad checking

for seed viability with his agricultural planting.Ā How could I have neglected something so basic

with my tree seed?Ā I tried a number of

mechanisms for storing and checking seed viability, and the most costly mistake

I made was drying out tree seeds, for instance acorns.ĀĀ I quickly realized that I could not treat my

tree seeds the way that my father treated his seed corn and seed oats.Ā Desiccation occurred to over 20 bushels of

carefully collected white oak seed that I had protected from critters and

planted to no avail.Ā I now know that

desiccated acorns are in fact dead and not revivable, so all tree seed must be

collected and stored so that it can be preserved until germination.Ā I discovered a very good book, Ag. Handbook

450, Seeds of Woody Plants in The United States,Ā that is now my "Bible" of seed

collection, treatment and handling.Ā It

is no longer published, but it is still possible to access the information on

the internet.ĀĀ I was so happy to find

information was already available and I didnÆt have to ōreinvent the

wheelö.ĀĀ (Incidentally, I now

steadfastly believe that the best storage place is still in the ground where

you want the tree to grow.ĀĀ Let me

repeat, if at all feasible,Ā the seeds

need to be planted as soon as possible.Ā

ThatÆs natureÆs way.)

Our county extension

director held a field day for individuals interested in planting trees.ĀĀ He was aware of my attempts and included me

in a 1-hour session at the end of the program.Ā

I decided to showcase dense planting of trees as well as my

nursery.Ā At this point in time, my

"radical thinking on growing treesö was not well known.Ā To use an anachronism, I was "kicking

over the traces." In other words, I rejected out of hand the ōbook

solutionö that strongly endorsed black walnut monoculture plantations.Ā I was definitely not in favor of those

plantations.

During the tour of my

operations, I responded to a great number of questions and received a lot of

strange looks.ĀĀ At a private moment at

the end of the meeting, the extension director jokingly asked me ōWhy don't you

quit being so darned stubborn and just do it the way it's supposed to be

done?öĀ The University of Iowa extension

director, who was also present for the tour, eventually included in his

pamphlet a short paragraph on the possibility of using thickly-planted seed.

The nursery project

lasted only 4 or 5 years.Ā The initial

nursery failures did not stop me.Ā They

instead just slowed me down.Ā I

eventually figured out how to reduce depredation of nursery bed seeding by

fencing, covering seed beds with poultry netting or hardware clothe, etc.Ā It was an extremely labor-intensive

undertaking.Ā Just as I appeared to have

learned how to grow the trees seedlings in a nursery bed,Ā another major problem arose.

My future forests were

growing in my nursery beds instead of my nursery bedsÆ stock growing in my future

forests.ĀĀ How could I transplant all of

these trees by myself?Ā I was growing

upwards of 50-60,000 thousand stems a year. The sheer quantity was a genuine

concern.Ā I had a short planting window

and no help.Ā The initial solution was to

have my wife drive the tractor while I planted the stems from our homebuilt

tree planter.

Incidentally, it was

also around this time we discovered that transplant shock was a major

problem.ĀĀ I tried to comprehend why we

as a tree planting community came to the transplant conclusion in the first

place. I assumed it had to do with carryover from coniferous planting

techniques.ĀĀ Most of my previous

problems could have been avoided with the simple use of seed direct because I now

know that seed that has sprouted in place and never been moved has the optimal

opportunity for terminal root connection.Ā

No amount of transplanting could improve that connection. The following

picture shows just how extensive the root structure is. This is a one-year-old

tree from a test plot, and by digging up this tree, we lost approximately 60%

of the root structure.

Ā

Ā

In early 1988, my

forester noticed my allegedĀ 1982 failure

and surprisingly termed it a success.Ā

Impressed with the form and growth of my walnuts, he approved my plan to

direct seed my deciduous trees in a future planting.ĀĀ Having a forester validate my plan gave a

legitimateĀ boost to my new method.Ā My goal to establish a 15.9 acre CRP planting

(half of the planting was deciduous and the other half conifers purchased from

the state nursery) was on its way to becoming a reality.Ā With the box elder and other so-called ōtrash

treesö I did a bit of nudging here and there in an effort to help my ōreal

treesö to form and grow.Ā This wild idea,

direct seeding of trees, continues to be an integral part of my planting

strategy.

I now know how to grow

trees from seed in my nursery and my forester has just approved almost 16 acres

being planted seed direct starting in the fall.Ā

Just how difficult could that be?Ā

The feedback from people with whom I shared my plan was certainly

mixed.Ā I received a lot of ōexpert

adviceö suggesting that my plan would lead to failure.Ā From many fellow tree farmers I heard

anecdotal stories about how this planting strategy had been tried, öbut the

critters took every seed.öĀ I was used to

failure, so why not try one more crazy idea?Ā

Somewhere in this approximate time frame Sandy and I made a couple of

train trips to PA to visit our kids and grandkids.Ā During one fall trip, the amount of acorns on

the ground made a dramatic and everlasting impression on me.Ā At one point during my frequent walks through

semi-forested areas near my sonÆs home, the ground was so covered that I could

not take even one step without crushing an acorn.Ā If only I could have transported all those

acorns to my place!Ā An even more amazing

revelation took place during our trip the following spring.ĀĀ The massive quantity of acorns that had lain

for so long on top of the ground or under leaf litter were all in the early

stages of sprouting and forming young trees.Ā

Those acorns were so numerous that deer, turkeys, squirrels, etc. could

not possibly consume them all.Ā Nature

had overwhelmed the critters.Ā I then did

some quick counting of test plots on my own land, randomly threw out the

rock,Ā measured a specified area around

the rock for several spots, and eventually made computations.Ā Even with the rough measuring, I estimated

that Nature had seeded and sprouted 50-60,000 stems per acre.Ā I then remembered a local lawn that I had

previously photographed.Ā I took a look

at the photos and discovered that the lawn was literally covered with small pin

oaks that had sprouted from the previous fall mast crop.Ā Thank you Mother Nature.Ā It can be done.

My district forester

drew up the planting plan, indicating where and how many of each species should

be planted.Ā This plan was a bit

different from his normal spacing tendency since it called for direct seeding

of 50% of the plantation.Ā I ended up

ordering 6,000 conifer seedlings from the Iowa State Nursery in Ames.Ā The conifers, along with a few silver maple

and green ash, were to be spaced approximately 8Æ apart within the rows and the

deciduous seed spaced 2-4Æ apart within the row.Ā This tactic gave me a projected number of approximately

15,000 stems on the entire plantation.Ā

Since I was still a bit unsure about germination and survivability, I

asked my forester to specify a minimum number required, rather than a fixed

number.Ā His eager endorsement of my

request both validated and solidified my developing planting strategy: to

alternate deciduous and coniferous rows of trees.

A shadow now hung over

my head.Ā Could I get this project off

the ground?Ā What should the next step

be?Ā It was time to put up or shut up.Ā Out of sheer necessity I became the world's

biggest squirrel, subsequently spending the entire fall gathering seeds from

the primary deciduous species, walnuts, white oak, and red oak. Other concerns

also came into play.Ā First, that 15.9

acre field at the time was in row crops, most of which was corn.Ā Second, 1988 was a drought year and my tenant

did not harvest until late October.Ā

These two factors forced me to abandon my much preferred leisurely

planting pace.ĀĀĀ As soon as harvest was

complete and the corn stubble was disked,Ā

I got to work, using an old 4-row corn planter marker to lay out the

plantation for the 2-stage planting.

Lasting more than a

week, the first stage was the fall planting of walnut, red oak and white oak

seed. Sandy drove the tractor with me riding on the tree planter dropping seed

down the tube by hand.Ā I really tended

to overplant and eventually just ended up holding a handful of seeds and

letting each one flow quickly down the tube.Ā

I ended up planting 40-50 bushels each of both red and white oak.Ā I had problems with the white oak since it

had sprouted 2-3ö pigtails and regularly got tangled as it dropped down the

tube.Ā Several pickup loads of walnuts,

equally tough since they were very black and mushy after being stored in gunny

sacks in the shade for a month and a half, were also planted.Ā In addition, hydraulic problems with my

tractor made regulating depth unreliable and inconsistent.Ā Ideally, optimal depth, measured from the

ground level down, should be 6ö.Ā The

extremely dry soil was also a major factor in depth control.Ā Even though I had done my own collecting and

the seed was therefore cheap,Ā I did my

absolute best in order to avoid a future replanting.Ā

The post-planting phase

was characterized by doubt and second thoughts.Ā

With everything seemingly riding on ōThe Big Planting,ö I became a

worry-wart and subsequently spent the long winter trying to convince myself

that success was imminent.Ā Everything

would work out, wouldn't it?Ā

The second stage began

in March, 1989.Ā I flagged the entire

area because the marker furrows had noticeably faded over the winter.Ā My seedling transplants could not be shipped

until late April, so on April 1,Ā Sandy and

I drove to the state nursery in Ames to pick up our 6,000 conifer trees.Ā Planting lasted 3 long days.Ā Sandy strained to aim for the flags that were

homebuilt and hard to see,Ā while I

strained my back leaning over on the planter counting ōone potato, two potatoö

so I could space the trees, but by doing so I tended to get closer rather than

wider spacing.Ā Due to the spacing tactic

I eventually ran out of conifers, so I ended up filling in with some of my

private nursery trees.Ā I then used a

borrowed 4Æ drill to interplant a cover crop of oats and timothy between rows.

Within a day or so we had approximately an inch and a half of rain.Ā This occurred right in the middle of the

1988-1989 droughts. It was to be the last substantial rain we would get for

many months.

For the rest of the

month the worrying just got worse.Ā I

just had to succeed, yet all I could see was the green of the conifers.Ā I checked daily, noticing a great number of

ordinary weeds starting, but nothing in the way of oak and walnut.ĀĀ I knew where the rows were, so I could do a

bit of hoeing and hand weeding.Ā I

quickly realized I had to mechanize the weeding process.Ā I purchased a 2-row corn cultivator that fit

on my 1952 John Deere B.Ā I used only 1

row of it, however, in order to cultivate shallowly, barely skimming the ground

and within about 6ö of the marked row during the first pass.Ā I was still holding my breath that those

little oaks and walnuts would start poking through.Ā When the first one did poke through,Ā a bit of hope arose.Ā Within a week's time, and with the exception

of the white oak, the number of seeds popping through the soil was

overwhelmingly gratifying to me.ĀĀ And so

began the hand weeding in earnest.Ā I was

absolutely amazed by the numbers of little walnut and red oak, but the white

oak remained a ōno show.ö

As the days went by,

the number of small trees popping up through the soil continued to grow

(although I was a little puzzled by the large separation in emergence dates of

those babies).Ā Within just a few weeksÆ

time, the growth on the walnuts and red oak was fantastic.Ā I did notice within the first month of growth

that deer were wandering through, but at the time I thought deer would not be a

factor since I had so many trees growing.Ā

My cultivation and hand weeding continued, but I was clearly losing

ground with the weeds in some areas.Ā I

was nonetheless extremely happy, knowing I had a future forest whose trees, at

least for the most part, were still 6-12ö tall (with a few 18-24ö trees mixed

in).Ā Granted, the rows were 8Æ apart,

but at least I finally had possibilities.Ā

In late June, I really

started to worry about my white oak since it comprised almost 50% of my

deciduous plant population.Ā To satisfy

my curiosity, I dug into the soil and found white oak mummies everywhere.Ā There were no signs of rodent

depredation.Ā In addition, and thanks to

the sprouts on the seeds I noticed before planting them, I knew the seed had

been viable.Ā My final diagnosis was that

the severe 2-year long drought had possibly left some traces of corn herbicide

in the soil that could have affected the sprouted acorn.Ā The only other possibility was that the

extremely dry soil had sapped the moisture out of the sprouted acorn.Ā The latter possibility seemed more plausible

since I had planted my red oak acorns at the same time and they had not

sprouted until the following spring during which significant rain and snow had

fallen.Ā The realization that 50% of my

deciduous plantation, the white oak, was a complete loss, was a hard pill to

swallow.

My original planned

plant population was projected to be 15,000 stems.Ā During that first drought-filled year of

planting I lost not only all of the white oak, but also over 50% of my conifers

(red and white pine).Ā Rather than

waiting until late April when the shipment was originally scheduled,Ā I decided to plant the conifers during the

first few days of AprilĀ This lucky

decision also changed my entire plantation plan.ĀĀ Even though the rate of germination was

still unknown, I estimated I still had, thanks to over planting, a population

of roughly 50,000 stems.Ā In the fall of

1989,Ā I spent a great amount of time

filling in the spaces between the living conifers.Ā Not know whether the conifers would live

another year, I used a shovel and dropped a nut or red oak acorn spaced every

foot within the conifer row trees.Ā I did

not have a readily available crop of white oak acorns that year.

In the late 80s I also

found that seed planted into certain vegetation could germinate and grow

through that vegetation.ĀĀ The growth was

certainly not as fast, but it would grow and within a few years it started to

flourish.Ā In this specific case, the

suitable vegetation was old-growth, perennial sod-forming blue grass that had

been left untended after planting the tree seeds.Ā It was planted using a no-till machine that I

fashioned out of an old no-till seed corn planter modified in such a way as to

accept smaller walnuts and acorns.Ā It

slit the grass and allowed the seed to drop into the opening.Ā The slit then quickly closed in zipper-like

efficiency.Ā The bent grass was the only

way to know where the seeds had been planted.Ā

The seed sprouted in the spring and, compared to the test rows,

thrived.ĀĀ My forester suggested spraying

a 2Æ-wide band on both sides of several rows in order to see what

happened.Ā The roundup killed the

bluegrass, but unfortunately also introduced daisy fleabane and goldenrod.Ā Compared to the bluegrass, these two weeds

were much more harmful to the growth of the young oak and walnut.ĀĀ As far as the competition for nutrients was

concerned, the exchange of mild competition (bluegrass) for a possible toxic

one consisting of goldenrod and daisy fleabane (both of which are perennials)

was alarming.Ā After approximately 10

years, the growth in the untended area was much more advanced than the growth

in the sprayed one.Ā I now also believe

that the lack of transplant shock was the primary variable that allowed these

small trees to eventually flourish.Ā This

casual attempt to satisfy my curiosity was, however, not a true test due to the

fact that throughout this period rabbits and deer continued to severely damage

these small plants.Ā Looking back at my

one previous planting (in the bluegrass by the creek 10 years earlier), I now

realize that the sod conditions were identical.Ā

By default then, the only real variable was the damage caused by rabbits

and deer.Ā It is from this experience

that I can now conclude that it is indeed possible to grow seeds into trees

through untended old growth bluegrass as long as they, the seeds, have

sufficient time to establish themselves.Ā

This conclusion is further proof that human intervention is not

necessarily always beneficial.Ā Perhaps

the best path to success is simply to leave nature alone and let it take over.

At about this same time

I became aware of the phenomenal growth of seeds ōplantedö by birds.Ā I noticed eastern red cedar seemed to

flourish in a patch heavy brome grass that had been planted on a newly graded

highway right-of-way 4-5 years earlier.Ā

Throughout the state, eastern red cedar is hard to establish as a transplant

in untreated brome.Ā This is especially

true during a dry season.Ā Where there

are power lines or fences and grass, in other words, where birds hang out,

there will be eastern red cedar in untreated brome.Ā This is an example of seed direct tree

planting.Ā I jokingly tell others, if you

want a juniper, just drive a stake into the ground (where birds will perch) and

move it around every couple of years. This method also works well with many

other species such as black cherry, mulberry, etc.Ā I mention this now only to illustrate the

difference between planting a seed and transplanting a seedling.Ā Due primarily to its root structure,

sod-forming grass seems to play a crucial role in the success of seed direct

and seedling transplant, and especially so in the first couple of years of

growth. (Non-sod forming grasses are far more deleterious to seedling

transplants.)

In the early 1990s, a

consulting forester and friend brought a client to view my 1988 direct

seeding.Ā By this time some trees in a

few areas had finally started to show substantial growth.Ā One thing that was quite noticeable was the

devastation caused by deer browse.Ā The

forester asked what I intended to do.Ā I

expressed little concern, answering rather flippantly that I would simply plant

more trees.Ā So my plan was to ōoutplantö

the deer, planting far more trees than the deer could possibly damage.Ā I soon had to eat my words as I learned that

the devastation was specifically caused by neither the number of trees nor by

the number of deer, but rather by the deer to browse ratio.

The year of 1990 I was

struggling to keep the growing trees with their heads above the

competition.Ā I decided I was going to

have to go the herbicide route so I originally started with a backpack sprayer

trying to maintain 1-2Æ weed free on both sides of the seeding.Ā Early in the spring prior to bud break, I

sprayed herbicide to keep grasses and broadleaf weeds from growing.Ā Later in the year I had areas where I used a

shield to protect the growing tree from herbicide drift and applied Roundup

where the pre-emergent had not been effective.Ā

Some of those rows were 1/2 mile long and carrying that 5-gallon

backpack sprayer was quite tiring.

I began to ponder how

to increase my numbers in the failed areas of the 1988 planting and I wanted to

do it mechanically without destroying trees already growing which is very hard

to do with large equipment with the arrangement of trees at that time.Ā I found a bumper crop of white oak acorns

nearby.Ā My original rows, spaced 8Æ

apart, consisted of alternating deciduous and conifers (of which 50% or better

were dead).Ā The white oak was

nonexistent in its original rows.Ā I did

not think it would be feasible to mechanically go back and spot plant the bare

areas because the amount of space required for maneuvering the machine was

simply too limited and I risked damaging too many small living trees.ĀĀ In several of the areas where conifers were

growing I eventually managed to hand plant walnut and acorns (both red and

white oak acorns).

Ā

I decided to use my

brother's nut planter to plant a row of white oak spaced 2Æ on either side of

the conifer rows, and then an additional row of black walnuts spaced 2Æ outside

the rows of white oak.Ā This arrangement

was repeated throughout the entire plantation. I very wisely took Sandy's

advice to do everything by myself, since the investment of time was

considerable.Ā I started by converting my

brother's 2-man potato/tree planter into a 1-man tree seed planter.Ā Due to my unskilled cutting and welding

techniques, I ended up making a lot modifications.Ā It was more of a ōbreak it and remake itö

style of modification.

This final "high

tech machine" was really nothing more than a comic book plow assembly

fitted on my tractorÆs 3 point attachment.Ā

This invention made a slight furrow that was held open by vertical

sweeps just long enough so that the seeds could drop down a PVC pipe and into

the furrow before being covered by a double length of log chain sweep.Ā (By the way, most tree seedsÆ only requirement

is viable contact with bare mineral soil.Ā

For some seeds, not even that much is needed.)

Ā

While planting the

first white oak rows,Ā I could detect

that I was doing some root damage to existing trees (the feeder roots are

extremely close to the surface), but it was a gamble I thought I had to

take.Ā This secondary planting was done

using a tremendous quantity of seeds (more than 50 bushels of white oak and

black walnut as measured by the pickup load).Ā

I was doing this by myself and driving the tractor as slowly as it would

go.Ā With a bucket of seed on the tractor

seat,Ā I stood sideways and threw

handfuls of nuts down the tube.Ā As I

found out later,Ā this planting strategy

left behind a sort of Morse code pattern of growing trees.Ā You know ģ the dot-dash thing,Ā because the tube often got plugged up with

squishy flattened black walnut hulls.Ā

The worst case of that was the next year finding 15 living stems ended

up being planted in one linear foot of row.Ā

Not good, but I could kill trees faster than I could grow them.Ā OSHA would no doubt have objected to my

steering the tractor with my behind just so that I could plant seeds

faster.Ā ōI was busier than a one-armed

paper hanger.öĀ This aphorism epitomizes

my routine.Ā I managed to finish this

project in the fall of 1991, but without really knowing for sure what I had

done.

The following year I

was amazed by the number of young seedling trees that had started to

emerge.Ā These extra trees did, however,

cause a few problems.Ā Due to patchy

herbicide application the year before, competition was rampant in the original

white oak total loss areas resulting in many of the younger trees

struggling.Ā In some areas, trees at

least 2 years old were shading the newly emerging seed.Ā In addition, the rabbit population

exploded.Ā As a result, the oaks were

severely gnawed off or girdled.Ā One day

that winter I was able to dispatch 39 rabbits in three, 15-minute increments

using a 22 rifle.Ā It was so cold,Ā I could stay out of my warm pickup for only 15

minutes at a time without losing feeling in my fingers.Ā My extra work still paid dividends though,

because quite a few of those add-on trees managed to survive.Ā Again, density as a planting strategy seemed

to prevail.ĀĀ

ĀĀĀĀĀĀĀ

I decided to use my riding

mower with my backpack sprayer rather than simply walking around with the

sprayer.Ā That was an improvement, but 16

acres was still a lot to cover,Ā so I

attached a 12-volt, 12-gallon tank to the riding mower tractor.Ā This modification really shortened the

spraying time, so much so that I was able to apply pre-emergent herbicide to

all the rows, and in a lot less time, by driving in the 4Æ- wide alleys.ĀĀ The reduced width of the rows also forced me

to use a walk-behind brush cutter rather than a 5Æ - wide brush cutter on the

back of my tractor.ĀĀ This cutter was

used when the height of some of the more vigorous broadleaf weeds started to

exceed the height of my trees.

I was beginning to

discover just how bad the deer problem was becoming, so I started to fence in

my trees with used, woven wire and posts.Ā

Working alone, I spent almost a year and a half building 8Æ woven wire

fences around 2 separate plots of trees (65 acres and 19 acres). The original

15.9 acres had been increased in size.Ā I

installed a CRP forestry addition to ease the fencing problem.Ā There is a world of difference between the

fenced and unfenced trees!Ā When a deer

managed to get in, it did not stay very long.Ā

It convinced me that the best defense for trees is a formidable fence.

I estimated in

1992-1993 that there were approximately 250,000 stems in the 1988 plot

(including the additional 4 rows on both sides of my conifer rows).Ā That was a large quantity of very small trees

and I loved it.Ā I started to notice such

things as leaf litter in the fall, much more shade on the ground, fewer weeds

growing and fewer sod forming grasses.Ā I

continued to fill in areas with extra trees every year.ĀĀ It was easy to gather ash seed, linden, or

hackberry by simply sweeping up by curbs or in parking lots.Ā I would then walk through the planting area

on a windy day and toss a handful of the seeds into the air.Ā I got wonderful dispersal and quite good

germination.Ā Most of the final filler

trees were either shade-tolerant or somewhat shade tolerant species.

In the spring of 1992,

my district forester asked me to give a landowner presentation in Amana, Iowa,

to a group called the National Walnut Council.Ā

Here, IÆve been growing trees since 1962 and IÆm just now discovering

groups of other people are doing the same thing!ĀĀ It opened an entire new avenue to talk and

associate with other tree growers.Ā I

started presenting at local clubs and groups.Ā

I then started to volunteer at different fair booths and other events

such as the Farm Progress Show.Ā These

experiences gave me the opportunity to make many new friends and gain access to

new sources of information.Ā Best of

all,Ā I could talk about something other

than a monoculture plantation.

I eventually began to

make presentations of my planting strategy at various woodland meetings. During

one such meeting a forester jokingly said, "Larry, you are preaching

forestry heresy." I guess I was, but I was starting to see results I

liked.Ā But more important,Ā my results seemed identical to those of

Mother Nature.Ā That is why she was and

continues to be the guiding light for my work with trees.

I want to plant enough

seeds so that the quantity of woody vegetation can very quickly outgrow

sod-forming grasses.Ā In reality, I want

a forest condition to start at 1-2Æ in height.Ā

It is hard to do, but not impossible.Ā

In the fall of 1992, I mowed and spread herbicide to kill the sod in a

5-acre area of creek bottom land that had a few standing box elder and old

growth hickories.Ā I thoroughly saturated

that area with a tremendous amount of seeds of all varieties.Ā Black walnut and red oak were the biggest

quantity (more than a pickup load of walnut in the hull and 25-30 bushels of

acorns). I can't remember all of the species I used, but black cherry and juniper

certainly dominated. I know for sure that at least 15 species were

planted.Ā My strategy was simply to

overplant.Ā These seeds were drilled in

with my homemade planter as I attempted to cover every square foot of

space.Ā I estimate that 75% of the space

was planted using this strategy.

The critters had a

heyday that fall, winter, and spring, feasting primarily on the acorns and

walnuts to such an extent that the area looked like a lunar surface with

craters everywhere.Ā I therefore assumed

that the seeds were gone.Ā In April,

impressive numbers of walnuts and oaks and others seeds were popping through

the soil, but to no avail.Ā The creek

flowing through the area left its banks 11 times during the growing season,

causing harm to almost every tree.Ā The

area was never flooded or under water for longer than 24 hours.Ā It was the attendant leaf siltation rather

than the flooded ground that caused the most harm.

That fall I replanted

with somewhat the same quantities and drill pattern, only this time I did not

use pre-emergent herbicide.ĀĀ I

confronted the same critter depredation as the previous winter, so once again I

assumed that there were no seeds in the ground.Ā

In early April, large quantities of reed canary grass sprouts showing

along with other weeds began to poke through the soil.Ā I patiently waited for my seedling trees to

appear.Ā As soon as that happened,Ā I immediately decided to broadcast Roundup,

all the while knowing that I would kill the newly emerged seedling trees.Ā The competition from grass left me no other

alternative..Ā Those later emerging tree

seedlings, however, were not affected.Ā I

spent the rest of the growing season hand weeding and hoeing as much as I

could.Ā

This is what it looked

like after the first two growing seasons.Ā

I am almost 6Æ tall and standing in the center of the lower photo.

I

was overjoyed to have the 6-8Æ stand of red oak and black walnut codominant

conditions after just two growing seasons.Ā

I thought I had solved the problem; however, not quite.Ā Below are pictures of damage caused by

rabbits in less than 2 weeks time.Ā

Picture

showing complete loss of the red oak due to girdling.Ā

This

picture shows how badly the rabbits damaged catalpa, also due to girdling.

If I had planted only

two species, my attempt would have been a complete failure.Ā As it was with the numbers of other species I

had planted, today it is still a forest.Ā

It just does not have the red oak component that I had anticipated was

very important for this forest.ĀĀĀ The

little red oak still leafs out in the spring, but gets chewed back every

year.Ā It is fighting a losing battle

because those little trees donÆt get enough sunlight to allow the leaf

production to contribute to their growth.Ā

(Incidentally, about that time I had numerous hunters tell me that if I

were to allow them to hunt the rabbits,Ā

they would solve my rabbit problem.Ā

I informed them that I had the rabbit problem because the hunters had

killed all my foxes and coyotes.Ā Natural

predators can never be replaced by hunters.Ā

Hunters operate only a few hours a day.Ā

Coyotes and foxes also do not put bullet holes in trees.)

In 1998,Ā I planted another 17.6 acre field of

CRP.Ā I was able to mow, spray, and plant

fairly early in the fall and with a tremendous amount of seeds.Ā I had a bumper crop of white oak and black

walnut. This was a triangular field where I planted the hypotenuse the first

year. The second year I had a great crop of red oak, so I planted by driving

over the previous small trees in another direction so as to minimize damage to

the previous trees.Ā The third year I

planted in a third direction with a great quantity of other seeds that I was able

to obtain for just the hauling. I now had a plantation comprised of mixed up

rows and species of trees.Ā It became

very hard to do any further mechanical work. I was able to use my backpack

sprayer during the season and keep most of the competition at bay.

That same time in 1998

I disked and broadcast direct seeded a 3.8 acre field with roughly the same

species mix.Ā I was not able to use my

backpack sprayer since I had no idea where little tree seedlings were coming up.

That was my last disk and broadcast direct seeding.Ā I found that the drill technique worked much

better for me.Ā Today, most of that 3.8

acre plot looks like a forest (just not as good as the drilled), but the

continual deer browse has stunted the growth.

In early 2004, I was

asked to participate in a test for a possible control of Acrobasis, along

with 3 other locations in Wisconsin.ĀĀ

This insect was destroying the growing tips of black walnut trees in

some locations.Ā I had some minor damage

with my own trees, so I agreed, but with one condition:Ā I could use seed direct.Ā Due to the risk of transplant shock, I did

not wish to participate if I had to use seedling transplants.Ā I hand planted a 0.6 acre plot of black

walnut using seed direct,Ā planting four

seeds (each seed spaced six inches from the stake) with all stakes being six

feet apart. The planting conditions were terrible since I had not had the site

prepared the previous fall.Ā I was able

to kill some of the early sprouting grasses with Roundup.Ā I used four seeds for each location in order

to guarantee at least one tree at each location (after accounting for

germination issues and depredation).Ā My

goal was to have at each location a living tree that was not a transplant. I

already knew that a transplant was not reliable to produce a great terminal to

start.Ā I had almost perfect

germination.ĀĀ A mid-May temperature drop

to 24 degrees turned all of the growing tips black. The amazing thing was that

almost all of those trees recovered with a single growing terminal.Ā One month later, all traces of frost

vanished.

The other three test

plots in WI were not so successful and lost a large percentage of their

trees.Ā I was asked the following year to

allow some of my extra plant material to be dug up to replant in WI.Ā I allowed 50 small trees to be removed by

digging.Ā I was not happy doing this

since digging that close to the surviving tree could still affect it.Ā I had planned on all my extra trees being

just cut off to keep from disturbing root structure of my test trees.

The originally planned

tests for Acrobasis were not carried out to due to the failure of the WI

plots.Ā In the first 2 years there was no

indication of Acrobasis in my trees.Ā

By the third year, though, I would not be able to brush the growing tip

with insecticide due to the fact that some of those trees had grown to over 11Æ

and were more than 3ö in diameter at ground level.Ā I no longer trusted myself on a step

ladder.Ā So between the quickly growing

trees on my plot and the failures in WI, we couldnÆt carry out the tests.

This test was

productive for me because for the first time I really became aware of the

massive amount of root that a tree could have.Ā

That first year when I was hand weeding around the small trees and

trying to remove the rhizomes of goldenrod, I often encountered a pencil-width

black walnut lateral in some cases as little as 0.5ö below the surface.Ā I now know that the base is very important to

the tree, so I am going to respect that.Ā

From now on, the only transplanting I will do is with clonal

material.Ā Below are pictures showing the

layout and 1st, 2nd and 3rd growing seasons of this plot.

Ā

Ā

Ā

Ā

In

2008,Ā I planted another large plot of

CRP, using my seed planter and basically as much seed as possible as well as

the same number of species.Ā Except for

the 3.8 acres, I have had all these plots fenced with 8-10Æ woven wire that

worked wonderfully well provided I kept them maintained.Ā Floods, windstorms, ice storms and other

weather-related events can wreak havoc on fragile fences.Ā The past 4-5 years I have not been able to

maintain the fences, so deer damage is still rampant.Ā There is no such thing as old enough trees

that the deer will not damage them.Ā The real

issue is deer-to-browse ratio.Ā Mine is

entirely too high.

My previous comments

serve as background, as insight into my attempts to grow trees over the past 50

years. I do not claim to have an answer to the question, ōHow can I grow a

black walnut tree that will become prime veneer quality wood?öĀ In fact, taking into consideration all the

different locations, climates and terrain in the United States,Ā I doubt that there is a definitive

answer.Ā There is no ōone size fits allö

strategy.

I know we had high quality

trees in this region when it was first settled in the mid-1800s. I want to have

them again.Ā We are on the boundary of

the Eastern forests and the Great Prairie. I believe my farm had both forest

and prairie conditions in the early 1800Æs, and I think the forested areas were

in the valleys and creek bottoms.Ā I have

tried to think about how I can replicate those forest conditions, primarily in

those areas on my farm.

Getting a tree to grow

is easy, but getting it to flourish is somehow a bit difficult.Ā I do not wish to pick winners and losers the

day I plant.Ā I am not planning to grow

and carefully groom a black walnut tree from the day I plant it to the day I

harvest it.Ā I do not have the capability

to instantly determine which tree out of the thousands I plant will be the one

I choose to harvest 80-150 years from now.Ā

I have seen entirely too many trees that looked great when they were 1-2

years old that suddenly, 10-20 years later, were not the quality tree I wanted.

There are simply too many variables involved in the life of the tree. Therefore

I want to delay the decision to a much later point in the treeÆs life which

trees to keep.

Instead of trying to

grow the tree, I try to create the conditions in which the tree will have the

greatest chance to reach that veneer quality.Ā

Those conditions are quite simply the ones that are contained within the

confines of a healthy, thriving forest.Ā

Such a forest is the only place I have seen that contains the highest

quality black walnut veneer tree. I just have to insure that I have the

quantity of whatever tree I want to harvest growing within the confines of this

forest.

Black walnut is

probably the easiest tree in the world to grow, but one of the hardest trees to

grow for gaining the highest quality wood.Ā

What we as a walnut growing group have done in the past is love our

trees to death through coddling, prodding and poking and wondering why the

patient is not getting well.Ā

Unfortunately, our trees do not respond well to the treatment of a

well-tended manicured park setting.Ā

A great, healthy

productive forest is not a thing of beauty in most folksÆ eyes.Ā By this I mean a manicured lawn with every

twig in place.Ā It looks messy to most

human eyes, but to ōjungle eyesö it's beautiful.Ā We do not want a rotting log on our front

lawn, but the healthy forest thrives on this sort of thing.Ā That is what forest succession is all

about.Ā Give the tree what it wants and

not necessarily what you think you want.

I am starting from a

cropland-prairie condition. Our greatest competitor in the initial stages of

establishing a forest environment is perennial sod-forming grasses.Ā Widely spaced walnut by itself does not

produce the shade required to defeat sod-forming grasses that are highly

competitive for nutrients.Ā I know that

many tree growers believe that mowing will help the plantation.Ā Mowing actually leads to a more vigorous

growth of these grasses. Mowing also introduces lawnmower disease (bark and

root damage).Ā How do I go from prairie

conditions to forest conditions as quickly as possible?Ā Dense shade is the most feasible.Ā I could cultivate or use herbicides to keep

the sod-forming grasses at bay, but that approach introduces some undesirable

side effects.Ā Both of these will keep

the areas between the desired trees as bare ground.Ā But this tactic in turn does not maintain

ideal tree root zone soil conditions.ĀĀ

Over time, however, both also tend to change the soil from a friable

condition to more concrete-like.Ā

ĀI want these forest conditions as rapidly as

possible.Ā I would like to canopy within

the first year if possible. That in itself dictates an enormous quantity of

trees, many more than I see being planted by most tree growers.Ā In my mind, the canopy stage is the start of

the healthy forest. That is where ideal conditions for the little trees begin.

They need that cool, moist soil in the root zone.Ā That is what canopy time provides.Ā I call this the ōIowa corn field

effect.öĀ I want to see if I can

replicate that in my forest.

I plan to direct seed

an ultra-high density companion planting to get this canopied forest in a very

short time.

Seed direct is very

important.Ā It allows the other two

ingredients to be easily applied quickly. A tree that grows from a seed has the

best radical to terminal ratio you can ever get.Ā Using our present methods, it is not possible

to economically grow a root of the transplanted tree that matches the root of a

direct seeded tree.Ā This logic may not

apply to the use of genetically superior trees unless we can somehow hybridize

a tree like we have our field corn. The root is the most important part of the

tree since it comes first. We just donÆt see it is all. Any and all problems

with seed direct that have occurred in the past can almost invariably be overcome.

The biggest problem is assuming that one seed equals one live, growing

tree.Ā That is just not going to

happen.Ā You must plant with quantities

of viable seed that will overcome these past failures.Ā Most of these failures are anecdotal.Ā I have yet to fail with viable seed planted

in quantities that can overwhelm the critters and elements.ĀĀ

There are two methods

of mechanically direct seeding.Ā I

mention only the mechanical methods since I doubt there is anyone who wishes to

plant the quantities of seed I am talking about using the back-breaking

shovel-and-drop-a-nut method.Ā I have

seen both methods work successfully.Ā

Disk and broadcast the seed is a fast way.Ā It does have drawbacks that I do not like so

I move on to the drill method.Ā I like

this primarily because I do not need to have all the seeds available at the

same time. There are machines now that can mechanically plant the seeds in

rows.Ā (Below, you can see my hand-made

planter which can keep 1 person very busy indeed.Ā The manufactured planters are far more

efficient for a single person to use.)

My seeds are still

planted with a primitive row machine. I also believe that a successful, healthy

forest may require several years of planting or introducing friendly species. I

no longer believe in once over the ground and you are done. That is not

natureÆs way.Ā Some differential planting

is invariably needed due to plant growth speed and available light

differences.Ā I have major problems with

two introduced grasses (canary grass and brome) so I like to know approximately

where the small tree will be emerging.ĀĀ

I get this when I have a row furrow.Ā

These grasses are extremely hard to eradicate by mowing just once,

spraying herbicide to kill the regrowth and fall planting of the seed. That is

due to the large quantity of dormant weed seed that inevitably remains in the

ground.Ā If I can see where the row is,

then I have a general idea where a tree might be in case rescue herbicide

treatment is needed later on.

The seed must be

viable.Ā Collection, storage, and

planting all must be in a manner maintaining viability of that particular

species.Ā The best storage container is

the earth, right where you want the seed to grow.Ā Once again, Agriculture Handbook 450 Seeds

of Woody Plants in the United States is an excellent reference for all of

this.

Seed direct has given

me the best chance to have young trees with the best root structure possible.

The high density is to ensure the quickest canopy possible. Black walnut alone

does not have dense enough shade to fully canopy (in a monoculture you can

still find perennial sod-forming grasses).Ā

You must have other species that will ensure the amount of shade.Ā Since I do not have the wherewithal to know

exact numbers of each and every species that should go into the ideal forest I

try to include almost every native species.

I want diversity and

most definitely not a monoculture which can lead to disease, insect problems

etc. I think certain trees like certain other trees for companions.Ā In my case, I have always thought my walnut

trees were very compatible with the maple (Acer) species.Ā You must closely monitor these fast growing

companion species early on.

Diversity to me does not

necessarily mean planting exclusively different species of trees that have

potential for harvest.Ā I will plant any

species of native tree that for that one moment in time is helping me create my

ōjungle effect.öĀ The ōgood tree-bad tree

dichotomyö only applies as helping or hurting my plan.Ā It has no relationship to a specific

species.Ā As an example of this, I have

had excellent results with the use of box elder to control grass in my

understory.Ā It can be dicey if you allow

this tree to get ahead of a sun loving variety.Ā

Another tree that I have used is the ditch cedar (juniper) which really

will reduce sod.Ā Ask any Kansas,

Oklahoma, or Texas rancher about that. They want grass and I want trees. I have

found I can kill trees faster than most people can plant trees.Ā 90 + % of the trees I plant will not survive

to harvest and are used strictly as a nurse tree.Ā This includes almost all of the pioneer

species, which I have used in the past 25 years.

ĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀ

I do not look at the

healthy forest as one level only.Ā There

may be several levels of canopies including the ground level ones.Ā I really shy away from bare ground. There are

many native forest plants and shrubs that are very beneficial to the healthy

forest condition. I consider most of these native plants beneficial unless I

can observe they are harming my so called target trees. I dropped the term

trash trees when talking about certain native trees. Instead I talk about

whether a tree is harmful or beneficial to my healthy forest at that one moment

in time of the forestÆs life.Ā

I want that forest to

start at the level of a few feet and that takes a great number of trees. LetÆs

call it the pyramid effect. I need a huge number of plants to completely shade

the ground at a low height and as the height of the pyramid goes up I need

fewer and fewer trees casting shade. It isnÆt all necessarily just the shade

that IÆm interested in.Ā I want minimal

wind blowing through this forest, especially during hot summer months. I want

that cool moist soil in the root zone.Ā

If that root zone soil becomes hot and dry the tree really stops

growing.Ā You will notice this in the

cupping of the leaves during these hot dry windy summers.

Extensive

shade is also beneficial for the boles of target trees.Ā Walnut trees shading other walnut trees is

not really effective.Ā In order to

inhibit the growth of limbs that can eventually contribute to defect in the

final log product, heavy shade is needed throughout the life of the tree.Ā The best veneer logs are grown primarily in the

deep woods.Ā Years ago while on a tour of

a veneer mill in Columbus, Ohio,Ā I asked

a log buyer where the best veneer logs could always be found.Ā He said he would never pay premium veneer

prices for logs if he could not determine that they had been grown in the deep

woods.Ā The boleÆs exposure to direct

sunlight played a role in its quality.Ā

These sage words of advice were good enough for me.Ā Seemingly this diminished quality had

something to do with the hidden epicormic sprouts which would show as a pin

hole during the

veneer

processing.Ā While helping a fellow

plantation owner thin a monoculture plantation,Ā

I noticed that the pole-sized trees that we had thinned had an extensive

number of protruding pins on the bole when the bark was peeled.ĀĀ I believe this phenomenon was due to

sunlight shining on the bole.Ā This

experience inspired me to try to grow a tall and fairly slender sapling as

rapidly as possible, meaning one still sturdy enough to support itself without

becoming a spring pole.ĀĀĀ In a less

densely populated plantation, wind can play havoc with a slender tree.Ā (Something that comes to mind is the seedling

protection tubes often used when growing trees.Ā

When the tube is removed, the tree just falls over.Ā I believe that the tissue of a sapling is

somehow strengthened by the gentle back-and-forth pressure provided by the

wind, which the use of the tubes has prevented.Ā

The tube serves as a modified greenhouse and greenhouse plants generally

have to harden off gradually after their transplantation into their permanent

environment.)Ā By thoroughly

over-planting an area resulting in a crowded variety of small trees where the

terminals of the target trees have full exposure to sunlight, then this

planting strategy should work.Ā But itÆs

one giant balancing act.Ā Success can be

achieved while the sapling still has a small diameter if the side branching

dies early from lack of sufficient sunlight.ĀĀ

Unfortunately, maximum growth can occur only if there is a maximum food

factory, which means lots of branches with leaves, so at this point the volume

of wood decreases, but theĀ quality of

wood increases.Ā This is a trade-off that

I gladly accept.

I

do not support manual pruning because the wounds seem to heal much slower than

those on a self-pruned tree.ĀĀ At some

point in time I started to pay close attention to the processes that can occur

when a branch naturally dies and falls off the tree. Nature shuts off the

nutrient supply to the branch when it stops performing as it should, in other

words, when, due to lack of sunlight, the branch with leaves stops sending food

to the main stem.Ā When this small

diameter branch falls off,Ā a small divot

is left behind.Ā The subsequent wound

repair tissue tends to grow into the divot and flush over, rather than bulging

out like the standard manual pruning found with either dead or living

branches.Ā I started to experiment with

small branches that had died on black walnut and red oak, and I found that

within a specific time frame, I was able to gently move the branch up slightly

and then down slowly and the branch would come out much like a cork out of a

bottle. The initial upward movement of the dead branch served to guarantee a

break of the lower attachment point in order to avoid a bark tear. It was

amazing how quickly that particular wound healed over, resulting in a wound

smoother than one caused by manual sawing or pruning. The sooner the wound is

smoothed over, the sooner it starts to produce possible veneer-quality wood.

Ā

Ā

ĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀĀ

As

soon as the area has developed a canopy, the stem count starts to diminish due

to stems not receiving adequate sunlight.Ā

(The black walnut must keep its terminal in full sunlight, otherwise it

will rapidly decline and die.)Ā At this

point, there is a significant decline in sod-forming grasses as well as an

increase in natural mulch due to leaf and twigs falling.Ā The forest soil starts to change to a more

friable form.Ā There should no longer be

a need to mow or use herbicides in order to control weeds, though utility and

access paths will still be areas of grass that will need to be mowed.

This

is what I do and what I project myself doing.Ā

I really want to try to imitate the way nature grows trees, though IÆm

trying to compress the time frame significantly.Ā I work very slowly, but not quite as slowly

as nature generally does.ĀĀ This paper is

not a DIY instruction sheet on assembling a forest in 3 easy steps.Ā I cannot state the exact quantity and types

of species needed for a specific plot of ground because I do not have that

knowledge.Ā I would rather think of it as

a gentle reminder to everyone that there is still a whole lot to learn about

growing quality trees.Ā I would like to

report, however, that it has been a most thoroughly enjoyable and rewarding

lifetime experience.Ā

Over and out!